As a 58 year old, married white man who was raised Christian, I “check off” most of the boxes on the Privilege Worksheet of Life. I’ve never been pulled over by a police officer for no reason; joggers don’t cross to the other side of the street to avoid me; I’m given the benefit of the doubt in virtually every situation in which I find myself. While some of my privileged brethren grew up believing they had “hit a triple,” I’ve always known I was “born on 3rd base”, and have benefitted greatly from my privilege.

Perhaps as a result, I haven’t always felt comfortable when talking about matters of diversity, inclusion, and equity as they effect my chosen profession, education. I understand the inequities in our society, but believe that I have more to learn by listening to those who understand these inequities personally.

But there is one group of persons I do feel comfortable addressing when it comes to these issues. So, consider this a message to my fellow old, straight white guys who are working in the schools.

Hey, guys: It’s not about you.

When discussions about systemic racism, or institutional biases, or societal inequities are happening around you, no one is targeting you individually.

No one is blaming you. They are trying to point out that the very systems that have been so welcoming, and advantageous, and accommodating to you, haven’t always been that way for everyone — especially our friends, relatives, and neighbors who are Black, Hispanic, Latinx, LGBTQ, women, disabled, or Muslim.

They also aren’t suggesting that you haven’t worked hard to get to where you are in life. Of course you have. Having privilege doesn’t mean you aren’t a hard worker. It does mean, however, that those without the privileges you enjoy may have worked just as hard (or even harder), and achieved less. Or been paid less for the same work. Or may not have been admitted to the same schools as you. Or been given the same consideration for a job, or a promotion, or a mortgage. Again, this isn’t your fault. But how you respond to these realities, and how you use the privileges you do have, says a lot about you.

We recently saw the Executive Director of the national association for music educators forced to resign as a result of making some very disturbing and ignorant comments about minority persons at a meeting of professional organizations; a meeting convened specifically to discuss issues surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion in the arts.

We recently saw the Executive Director of the national association for music educators forced to resign as a result of making some very disturbing and ignorant comments about minority persons at a meeting of professional organizations; a meeting convened specifically to discuss issues surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion in the arts.

Now, in a textbook example of not learning from someone else’s mistakes, the editor of a state music education journal has attempted what can only be seen as an effort to exonerate the executive director with an op-ed published in School Music News. The author suggested a number of “excuses” for why there isn’t more diversity in school music programs. While most of these excuses don’t really merit a response, let me try to reply to some of them with a few thoughts.

- “…assimilation into today’s American culture is much different than it was in the 1950s and 1960s”. No one who has studied multi-cultural education or culturally-relevant pedagogy has seriously suggested that immigrants should “assimilate” into another culture for a long time. We no longer expect immigrants who come to the United States to change their names, to not teach their children to speak their native languages, or to abandon their cultural traditions — and we look back at the time in our country when immigrants were encouraged to do these things with shame. Today, we believe that it is our differences in a pluralistic society that provide the strength and vitality that distinguishes America’s cultural heritage.

- Students who require “academic intervention services” and “forced remediation” make it more difficult to form music ensembles that reflect a diverse student population. To use a student’s need for special education services as an excuse to not diversify our student population in school music programs is reprehensible. Research shows that students who are placed in classrooms with other students with a wide range of abilities learn better, develop better, and have more open-minded attitudes about students with disabilities than their peers who are placed in more “tracked” classrooms.

- A “lack of encouragement and support from the home” from families from diverse cultures makes it hard to have diversity in school music programs. Blaming a lack of school music participation from students from diverse cultural backgrounds on a lack of support from their parents is simply unacceptable. I’ve been teaching since 1980 and have still not met a parent or guardian who didn’t want the best for their child. Placing the blame on parents and families for a lack of diversity in school music programs ignores the responsibility on the part of schools to reach out to all families, and to provide offerings that are of interest and relevant to all students.

- “The media’s fixation on highly paid athletes and the attention given to sports and the lack of coverage for the performing arts” makes it difficult to attract a diverse student population for music programs. Blaming this issue on sports? Come on…this is just intellectually lazy. Again, it evades responsibility for recruiting and supporting a more diverse population into school music programs and for designing classes and other offerings that would appeal to a more diverse group of learners.

Underlying both of these situations seems to be the need to provide excuses for the lack of diversity in our student populations, teaching workforce, and curricular offerings rather than suggesting solutions that proactively address this lack of diversity.

Both the executive director and the editor were correct in their observations that we have some work to do in creating a more inclusive profession in our schools. To do so, we need to adopt policies that are designed to create a more welcoming environment for all members of the school music community, such as:

- Enhancing and expanding music offerings in middle and high schools beyond the traditional band, orchestra and chorus model — including more folk, popular, world and vernacular music-making classes, more technology, and more creative music making (song writing, improvisation, composition, arranging, creating cover tunes) in the school curriculum.

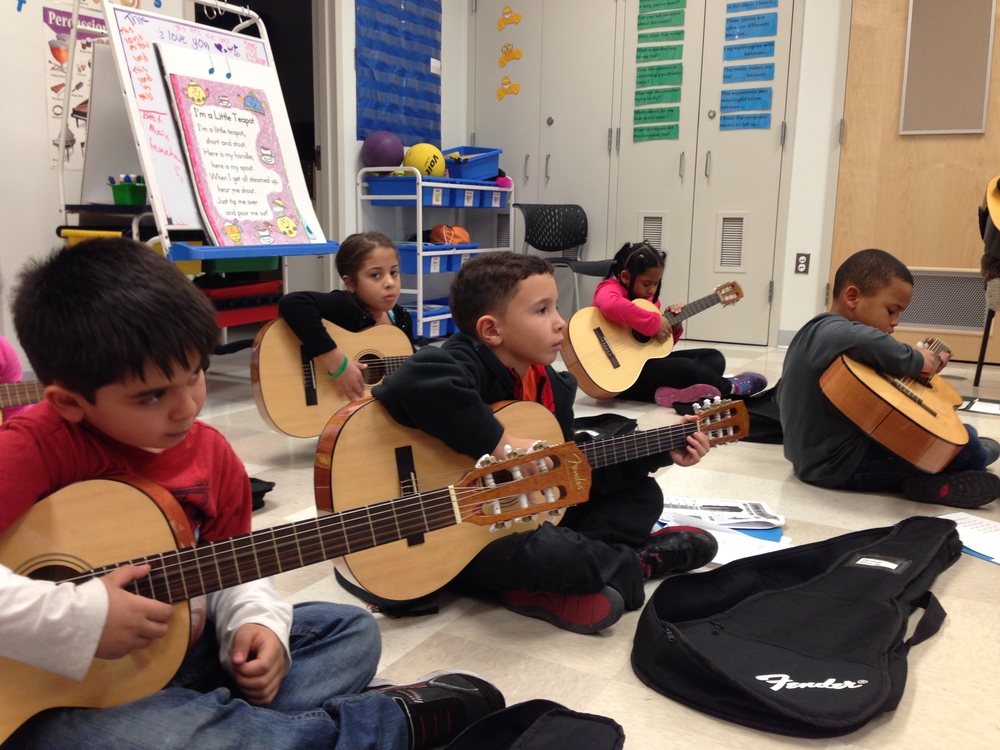

- Making sure that our bands, orchestras and choruses “look like” the population of students in the schools in which they exist. That may mean providing instruments for students who can’t afford to rent them, and subsidizing private lessons.

- Improving access for urban and rural students so that they have the same number and quality of music offerings that their peers in more affluent schools enjoy.

- Providing scholarships for summer study for underrepresented minority students, offering free registration for solo and ensemble events for students from low Socio Economic Status (SES) schools, and working to identify and support minority students who are interested in becoming music teachers.

- Music education associations should examine their lists of “required solo and ensemble music” to make sure that black, Hispanic, Indigenous Peoples, women, and LGBTQ composers are represented on these lists.

- Conference and festival coordinators should be encouraged to invite a diverse roster of guest conductors and clinicians to work with students at regional and all state festivals. These people are often important mentors and role models for our students, and we need to make sure that our students “see” persons who look like them on podiums and in classrooms at these events. It is also important for “majority” students to have the opportunity to work with a more diverse array of guest conductors and clinicians who often bring unique backgrounds and perspectives to their teaching.

- Establishing recruitment programs to identify promising young minority music teachers and encouraging these teachers to pursue leadership positions in their local, state and national music education associations.

- Reducing or eliminating obstacles in our college and university music programs in terms of audition procedures that make it more difficult for minority students to be accepted to these institutions to pursue music degrees.

Our schools and colleges must change their mindsets and finally begin to consider the issues of race, diversity, equity, and inclusion as opportunities for growth and understanding, rather than problems to be solved. Our diversity is a strength, not a weakness.

And an education in music is not a privilege; it’s a right, for every child.

[CC image credit: Trade News Singapore | via Wikimedia Commons]