This transgender woman is on a lifelong journey to express her authentic self.

This is part of a story series about the lives of transgender people. Read the introduction here.

It was the summer of 1964. Char Davenport, who was eight years old, was sitting with her father on the front porch. At the time, she says, she didn’t think of herself in terms of sex or gender — she didn’t relate to the male body she’d been assigned at birth, but at her young age, she didn’t think much about it one way or another.

It was the summer of 1964. Char Davenport, who was eight years old, was sitting with her father on the front porch. At the time, she says, she didn’t think of herself in terms of sex or gender — she didn’t relate to the male body she’d been assigned at birth, but at her young age, she didn’t think much about it one way or another.

She just knew she didn’t want to play baseball.

Her father had other ideas. He was determined she’d play baseball, Davenport recalls.

I didn’t want to play baseball and I was distraught and in tears. I was adamant. I told him I’d cheer on the team or keep score or work concessions. But I did not want to play baseball.

He finally said, ‘You’re going to play.’

I said, ‘Why don’t the other girls have to play?’

He finally lost patience with me and said, ‘You’re not a girl. You’re a boy.’

I was so panicked and I said, ‘I am a girl!’

We went back and forth, and I told him I wanted to be like this girl I knew. And he said, ‘You don’t want to be a girl. Girls are stupid.’

I remember looking at him and thinking I’d lost this argument. I knew I’d lost myself at that moment, that I was gone. That was the end of me. I didn’t think of it in those terms yet, but I knew it was a huge loss. I remember thinking, ‘Who am I? Why is this happening? What’s wrong with my dad — why can’t he see me?’

For many years after, Davenport’s authentic self wasn’t visible to anyone, although she always knew who she was. But like so many transgender people, she tried in vain to fit into the gender norms society assigns to people born as male.

After high school, in 1974, Davenport joined the U.S. Navy, where she served as a petty officer second class. It was in the 1970s that she first heard the term transgender, or transsexual, which was the common term in those days. She made some trans friends and felt comfortable being with them. A friend in the Navy was transitioning in secret, and would share her hormones with Davenport. She tried to transition in secret, too, but constant deployments made that difficult.

In the 1980s and 1990s, she tried herbal supplements to transition, which made her sick. Trying to self-prescribe hormone therapy is risky, but like many transgender people, especially at the time, Davenport didn’t have a lot of choices.

“I thought I could transition without anyone knowing,” she says. “I didn’t have a plan. I was just going to transition and no one but me would know and that could be okay or something. I was living two lives.”

Years later, in 2003, after earning her degree, Davenport was teaching high school in New York and started talking to a therapist. She was ready to transition, and already had a closet full of female clothes in addition to her male wardrobe.

“I’d talk to some of my students about it,” she says. “They knew who I am and I needed to be authentic. I was living a lie.”

Davenport was about to start hormone replacement therapy (HRT) under medical supervision when she collapsed due to a brain hemorrhage caused by a birth defect. While she was in the hospital recovering from multiple brain surgeries, her family moved her out of her apartment. When she got out of the hospital, all her female clothes were gone.

“When I asked about my clothes,” Davenport recalls, “no one knew a thing.”

She halted her plans to transition while she recovered. When she returned to teaching, even though she wasn’t transitioning yet her superintendent found out about her plans. He told her he was going to fire her for “endangering the health and welfare of minors.”

“I looked at him and said, ‘You know this is wrong and if you fire me in the middle of the school year I’m going to sue you,’” Davenport says. “The fact is, I didn’t want to teach at a school district that didn’t want me. I said I’d quit at the end of the year.”

It wouldn’t be the first time she was fired for being transgender. Davenport has received numerous honors for her teaching, including being named High School English Teacher of the Year in New York, so her work performance clearly isn’t an issue. After a more recent dismissal, Davenport filed a sex discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which ruled in her favor. Further litigation is pending.

By the time she’d fully recovered from her brain surgeries, in 2013, Davenport made the decision to begin transitioning again — and to come out to the world. She’d moved back to Michigan and started working with a therapist, Davenport recalls.

I walked into the therapist’s office and said, ‘I can’t keep doing this. I need to get on hormones or something.’

The therapist looked at me and said, ‘You’ve waited long enough’ and he wrote the prescription right there.

I cried when he said that. I had no idea it would be that easy for me. It’s not that easy for a lot of people but it was for me. I had the right doctor at the right time.

Not everything has been easy for Davenport. Because of anti-trans discrimination, she hasn’t had a full-time job in 12 years, but she feels fortunate to have been consistently employed part-time, currently as an adjunct college professor.

Over the years, Davenport has faced violence, like far too many transgender women. More than once, she’s been beaten to the point of losing consciousness, and faced a frightening encounter at a rest area bathroom.

I was coming out of the women’s room and my voice gave me away. Some guy said, ‘Dude, what are you doing in there?’ The guy squared his shoulders and came at me. He could have kicked my ass.

Even though I was really scared, I looked at him and said, ‘You’d better hope you win.’

He just said I was lucky that time and walked away.

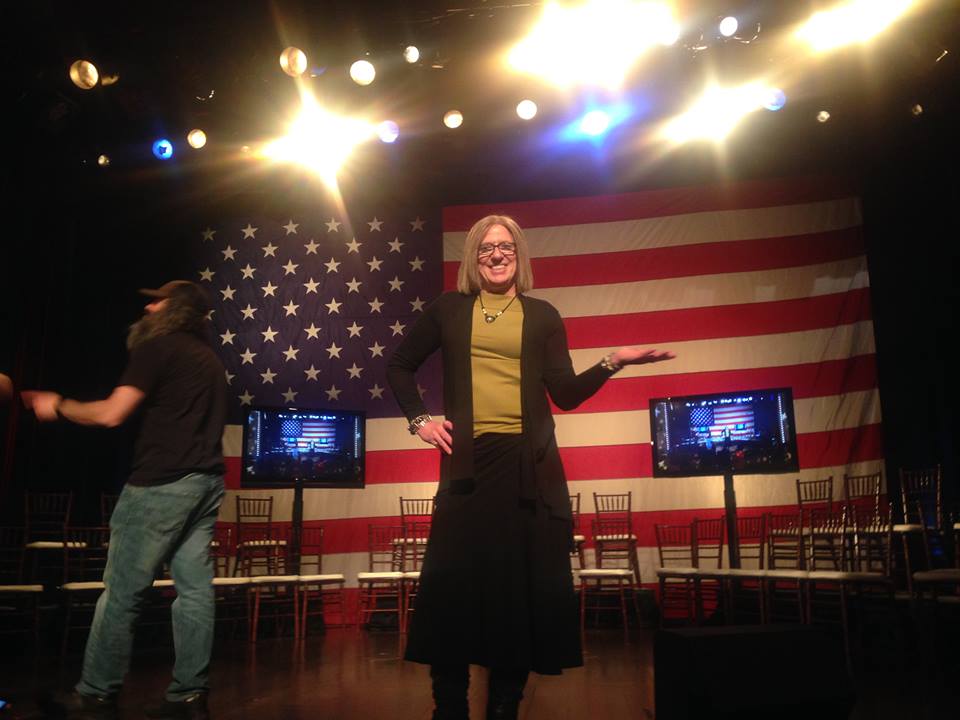

Incidents like these have driven Davenport to activism for both the transgender and broader LGBT communities. In addition to being a participant in the ACLU of Michigan’s Transgender Advocacy Project, she’s helped pass non-discrimination ordinances across the state and works with the National Center for Transgender Equality. She’s gone to Washington, D.C., to lobby her representatives and has been part of the effort to expand protections under Michigan’s Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act (ELCRA) to include LGBT people. She also facilitates a transgender/non-conforming/non-binary group meeting in her hometown of Bay City, Mich. Due, in part, to her activism, she was invited by the Bernie Sanders campaign to attend the Sanders/Clinton Town Hall debate in Detroit.

Incidents like these have driven Davenport to activism for both the transgender and broader LGBT communities. In addition to being a participant in the ACLU of Michigan’s Transgender Advocacy Project, she’s helped pass non-discrimination ordinances across the state and works with the National Center for Transgender Equality. She’s gone to Washington, D.C., to lobby her representatives and has been part of the effort to expand protections under Michigan’s Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act (ELCRA) to include LGBT people. She also facilitates a transgender/non-conforming/non-binary group meeting in her hometown of Bay City, Mich. Due, in part, to her activism, she was invited by the Bernie Sanders campaign to attend the Sanders/Clinton Town Hall debate in Detroit.

Davenport knows that being a visible transgender woman has its risks. She cautions other transgender people to think carefully about what that means.

I choose to be visible because that’s my defense. If anybody’s going to do anything to me, they’re going to do it in broad daylight and everybody’s going to know it. But choosing visibility is not something to be taken lightly. It can be dangerous. On the other hand, you want to be visible because you want to be your authentic self.

Davenport feels a deep sense of contentment, because she’s no longer trying to be someone she’s not. She’s now making arrangements for sex reassignment surgery, which is important to her, largely because she’s always been attracted to straight men. But it’s more than that, she says.

I think I have to keep pushing forward. Because I’m in my 60s and I don’t want to wait anymore. I wanted to do this so many years ago. I’m in awe of young transgender people I see who are out, and I think, ‘How did I not have courage at their age?’ More than anything in the world, I want the surgery. But if it never happens, I will always know who I am.

Davenport’s family knows who she is, too, and most of them have accepted her transition. Including her father, who Davenport had a challenging relationship with nearly until the day he died two years ago. Already presenting as female, Davenport went to visit him in the hospital, where he was being treated for cancer.

She recalls what she considers the second part of the story about playing baseball when she was eight years old.

I walked in and he didn’t recognize me at first, then his eyes lit up. He said, ‘It’s you — it’s really you.’

I opened my arms and said, ‘Yeah’ and he said, ‘Oh my God, you’re beautiful!’

Then he told me that all these years, he’d been asking God for help on this, for God to come into my life and show me the truth. I braced myself for the disappointment of what I thought he was going to say.

But instead, he said, ‘And then it hit me. I was praying for the wrong thing. I should have been praying for God to explain to me how I can love and accept you. It’s going to take time, but I don’t have time.’ And then he took my hand and said, ‘I love you.’

For her father to love her as she is — and not for who he wanted her to be — is something Davenport says she will always carry with her.

“I look at everything in my life — this journey I am on — and I knew I had to do this for myself,” she says. “And I’ve never been so happy.”

Watch for additional stories in this series, coming soon. Read all the installments HERE.

[Photos courtesy of Char Davenport.]