Today’s guest post was written by my new friend Sally Tyler. Sally lives in Washington, DC. and is a public policy analyst for a national labor union, who spent time in Wisconsin in 2011, and who occasionally reads poetry.

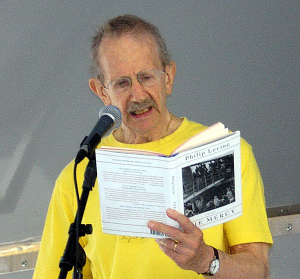

She writes today about Philip Levine, a U.S. Poet Laureate who died last month. Levine is best known for his poems about laborers and the working class. As Sally writes, his loss is a loss to the labor movement as a whole.

Enjoy.

Philip Levine, U.S. Poet Laureate 2011-12, who died in February, said that he began writing poems about the people who worked alongside him on the line at Detroit auto plants in the 1950’s because they were “voiceless.” I think Levine would have probably admitted that workers were always saying something, but that not enough people bothered to listen. And that is the genius of his life’s work: Levine gave voice, in a way that made readers pause to listen, to the strife, aspiration and resignation embodied in workers’ relationships to their jobs. His death comes at a time when fewer champions choose to lift up workers’ voices, and fewer still are willing to listen.

Philip Levine, U.S. Poet Laureate 2011-12, who died in February, said that he began writing poems about the people who worked alongside him on the line at Detroit auto plants in the 1950’s because they were “voiceless.” I think Levine would have probably admitted that workers were always saying something, but that not enough people bothered to listen. And that is the genius of his life’s work: Levine gave voice, in a way that made readers pause to listen, to the strife, aspiration and resignation embodied in workers’ relationships to their jobs. His death comes at a time when fewer champions choose to lift up workers’ voices, and fewer still are willing to listen.

The titular poem in Levine’s What Work Is collection (winner of the 1991 National Book Award) tells of standing in the rain waiting for work at a Ford plant, when the poet mistakenly thinks he sees his brother ahead of him in line before remembering that his brother, an aspiring opera singer, is “home trying to sleep off a miserable night shift at Cadillac so he can get up before noon to study his German.”

But even as the poet realizes it is “someone else’s brother,” he sees “the same sad slouch, the grin that does not hide the stubbornness, the sad refusal to give in to the rain, to the hours wasted waiting…” It is both a beautiful tribute to the love he feels for his twin brother, who commits himself to grueling and soul-deadening work for the chance to pursue his art; and a polemic about recognizing a fellow worker as a brother.

David Baker, poetry editor of the Kenyon Review, described What Work Is as “one of the most important books of poetry of our time. Poem after poem confronts the terribly damaged conditions of American labor, whose circumstance has perhaps never been more wrecked.” He was right about the book, but wrong about that time being the nadir of the American labor movement, as he did not anticipate the bloodletting workers would endure over the next quarter century.

Levine’s own Detroit has become a poster child for the pummeled American worker. The city was recently able to lift itself out of bankruptcy with something loftily referred to as the Grand Bargain, which will, among other things, cut retiree pensions for city employees. (What apparently makes it grand is that it supersedes the Ironclad Bargain workers thought they had made with the city regarding promise benefits such as pensions, in exchange for years of their labor).

Even though the Michigan state constitution prohibits the reduction of retirement benefits once established, a federal bankruptcy judge recently ruled that the Detroit city workers’ pensions could be cut, so the deal moved forward. On March 1st, approximately 12,000 city retirees, who earn on average $19,000 annually through their pensions, saw their monthly check reduced by 6.7%.

And, though unions fought for the pension benefits of Detroit city workers, they are not in the same position to fend off the ax that they were when Levine first began giving recognition to workers’ stories. When Levine worked in auto plants in the 1950’s, one in three American workers was part of a union.

Union membership decline has been steady since that time due to a variety of factors, including the off-shoring of American manufacturing; but the trend has accelerated in recent years due to the imposition of state right to work laws, promoted by ideologues intent on decimating labor. Indeed, even Michigan passed such a law. In 2014, the first full year of right to work there, union membership fell sharply from 16.3% to 14.5% of workers.

This week, a right to work bill became law in Wisconsin. On February 25th, the day it passed in the state senate, more than 200 citizens, mostly workers, waited in line for hours for their chance to testify against the bill. But committee chair Steve Nass abruptly halted citizen testimony due to a perceived “credible threat that peaceful protest might disrupt the hearing.” So, rather than take the chance that the hearing might be disrupted, he simply ended it; effectively silencing the voices (on that day) of those who dissented.

This policy of attempting to silence opposition voices is reinforced by Gov. Scott Walker’s recent comments at the Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) conference offering his track record of “taking on protesters” in Madison as evidence that he could effectively combat ISIL, and his comments at a major donor dinner in New York City (reported by the National Journal), in which he identified Reagan’s firing of striking PATCO workers as being the most effective foreign policy move by a chief executive in recent memory. No, he did not directly call lawful protesters and trade unionists terrorists. And true enough, there is a long tradition of feeding rhetorical red meat to the base in primaries that modulates into chicken cordon bleu for the generals. But still, America; Walker has made a statement about tactics, giving fair warning that for those who dare to raise their voices in dissent, he would rather annihilate than engage.

And there are policies beyond state right to work laws that attempt to silence workers’ voices. Though he had not run on an anti-union platform, Gov. Scott Walker foisted Act 10 on the people of Wisconsin, immediately following his 2010 election. The act prevents public sector unions from bargaining over pensions, health coverage, safety, hours, sick leave or vacations – the basic foundation of what workers expect from a union.

Walker’s sneakily-timed December surprise morphed into a ruinous budget bill in early 2011, leading to worker-led protests in Madison which created reverberations around the world. Students and teachers and workers came from throughout the state, eventually joined by supporters from around the nation, raising their voices in opposition to Act 10. Long after the budget was enacted, a committed group of protesters continued to assemble daily at the capitol; where state police, acting on the governor’s authority, eventually began to arrest them for the crime of singing. Yes, singing.

The steadfast determination of Walker and Republican state legislators, spurred on by anti-union groups like the Club for Growth, to ignore public opposition can be seen as a willful refusal to hear the voice of workers. But would Levine have said the workers in Madison were voiceless?

They were certainly noisy (Look Ma: All that time you said was wasted in the drum circle finally paid off), but there was no Gideon’s trumpet among them and the walls of the capitol did not tumble. As powerful as protest can be in shaping social change, having a seat at the table and a say over the conditions which most impact us remains the bottom line as a measure of workers’ voice.

This intentional deafness toward workers continues, frequently masquerading as muscular policy decisions in tough times. Buoyed by what he views as the success of Detroit’s so-called Grand Bargain, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie recently installed an emergency manager in Atlantic City to steer the city out of bankruptcy. His decisions are intended to override those of democratically-elected officials and short-circuit the collective bargaining agreements of public sector unions. It doesn’t take the visual acuity of a superhero to see that some elected leaders use any hint of a fiscal crisis as an opportunity to decimate unions.

But it might take someone with Levine’s clarity and depth of vision to adequately give voice to the situation. A poet inspired by Levine would forego the showier circus of an elected official who proudly bellows at a constituent to “sit down and shut up,” or the satire-ripe scenario of a political hopeful desperately trying to give the impression of foreign policy experience by conducting a mission to conflict-torn London, in favor of telling, in plain and measured language, the quieter story of how a retiree earning $19,000 a year decides what to give up when his pension is cut by almost seven percent. It’s not reality TV sexy, but it is grown-up and heartbreaking. And the calculus required of that decision should hit us like a blow to the solar plexus, if we are listening.

Where to find a new Levine? The career trajectory of a poet is rarely linear. Beyond the varied life and work experience which informs the best poetry, where might someone hone his instrument to give rise to the 21st Century worker’s voice? Before and after his time on the assembly line, Levine studied at some of the Midwest’s finest public universities, including Wayne State and the University of Iowa. State universities, however, may not provide such fertile ground in the future.

Walker recently announced a budget proposal which slashes 13 percent in state support from the University of Wisconsin. Not satisfied to diminish those noisy students and professors who joined union members in the halls of the capitol to protest the elimination of collective bargaining rights by defunding their education, Walker proposed deleting key components of the university’s mission statement, including “to educate people and improve the human condition” and “to serve and stimulate society.” (Faced with immediate public backlash, and increasingly sensitive to how his actions will play on the national stage, he withdrew plans to change the school’s mission). But still, as pollsters scramble to help candidates reframe their statements to hit the sweet spot in public opinion, it might be wise for us all to remember the original intent.

And while we wait for other poets to stand in his shoes, we can turn back to Levine’s work. From 1970, Levine’s Detroit Grease Shop Poem speaks in eloquent simplicity about what it means to be on the job:

Detroit Grease Shop Poem

Under the blue

hesitant light another day

at Automotive

in the city of dreams.

We’re all there to count

and be counted. Lemon,

Rosie, Eugene, Lois,

and me, too young to know

this is for keeps, pinning

on my apron, rolling up

my sleeves.

The poem stands as a stark counterweight against the prevailing mentality that only high-flying entrepreneurs and bosses are worthy of economic rewards, because they have made investments and taken risks. It reminds us that workers make an investment every day just by showing up. And by noting that workers are in it “for keeps,” it underscores that workers also take risks, in the form of foregoing other opportunities, closing the door to what might have been for the reality of what is in front of them.

Indeed, one of those Detroit retirees who just had his monthly pension check cut recently told a reporter that he thinks frequently about family gatherings he missed to plough snow and pick up trash for 30 years at the Department of Public Works. He made an investment and took risks in doing so, stepping up to his side of the bargain. The previous bargain, that is; before they changed the rules after he had already made it to the finish line.

A poem like Detroit Grease Shop Poem merely asks us to pause and consider the worker. A small thing, perhaps, but all too lacking in many of the most significant policies, decisions and transactions developed in our midst, and in our names. Though Levine’s voice has been silenced, maybe others will take up the cry.

[CC photo credit: David Shankbone | Wikimedia Commons]