Historic downtown Chelsea

As you look at the photo of downtown Chelsea above, imagine 80 gravel trucks a day, 6 days a week rumbling through the middle of it and then back again after they dumped their load. That’s one truck every 4 minutes during daylight hours and that’s the reality of what will happen if McCoig Gravel, a subsidiary of Thompson-McCully, is issued a special use permit and a mineral mining operations permit by the Lyndon Township Board. Janet Cunningham, who inherited the property from her late husband Donald, wants to sell off to McCoig so that they can build a gravel mine north of Chelsea. The gravel will then be hauled south, right through the middle of the village since their is no alternate route, to be processed south of town.

The only two parties that seem to want this mine are Ms. Cunningham and Thompson-McCully. Residents are against it and turned out in huge numbers at the first public hearing. The local Chamber of Commerce is against it. The Chelsea Downtown Development Authority is againast it. Lyndon Township and Chelsea City elected officials are against it. Environmental groups are against it — the 158-acre area contains extensive wetlands along with Stofer Hill, the highest point in the County which will become a 55-foot deep lake after operations cease in three decades.

In fact, you are would be hard put to find anyone other than those who will enrich themselves if the mine is allowed who want these permits to be granted.

However, Lyndon Township officials are fighting an unfair fight due to actions taken by Michigan Republicans soon after they took control of the state legislature in 2011. The original law that governs permitting of gravel mines such as this is the Michigan Zoning Enabling Act of 2006. This law shifted the burden of proving there will be no adverse impacts from a new operation away from the applicant for a zoning variance which allows activities to be conducted in a zoned area other than those specifically allowed by the local municipalities zoning regulations. Instead, the local municipality must prove that it WILL have an adverse impact. The law sets forth very specific and limited criteria for what can be used to deny a permit, criteria called “very serious consequences”. The municipality must prove that there will be a very serious consequence on one or more of the following:

- The relationship of extraction and associated activities with existing land uses.

- The impact on existing land uses in the vicinity of the property.

- The impact on property values in the vicinity of the property and along the proposed hauling route serving the property, based on credible evidence.

- The impact on pedestrian and traffic safety in the vicinity of the property and along the proposed hauling route serving the property.

- The impact on other identifiable health, safety, and welfare interests in the local unit of government.

- The overall public interest in the extraction of the specific natural resources on the property.

In 2010, a court case in Kasson Township in the Leelanau peninsula, Michigan’s “pinkie”, overturned this aspect of the law, putting the onus back on the permit applicant. In 2011, Republicans passed House Bill 4746, once again putting the burden back on municipalities.

This is the situation that Lyndon Township finds itself in. And the neighboring City of Chelsea which will bear the brunt of the huge surge in heavy industrial truck traffic along M-52, a two-lane road which goes right through the middle of town, can do little to help. The law is set up to benefit the mining companies like Thompson-McCully who have far deeper pockets than local municipalites and are willing to fight in court for as long as it takes. The case the initially overturned the “very serious consequences” portion of the Zoning Enabling Act, Kyser v. Kasson Twp, has been going on for ten years. The local township has been forced to spend nearly a quarter million dollars fighting it and only this week did a judge side with their decision to deny a gravel mine permit in an area outside of their gravel mining district. That case may not be over yet if the decision is appealed to the state Court of Appeals.

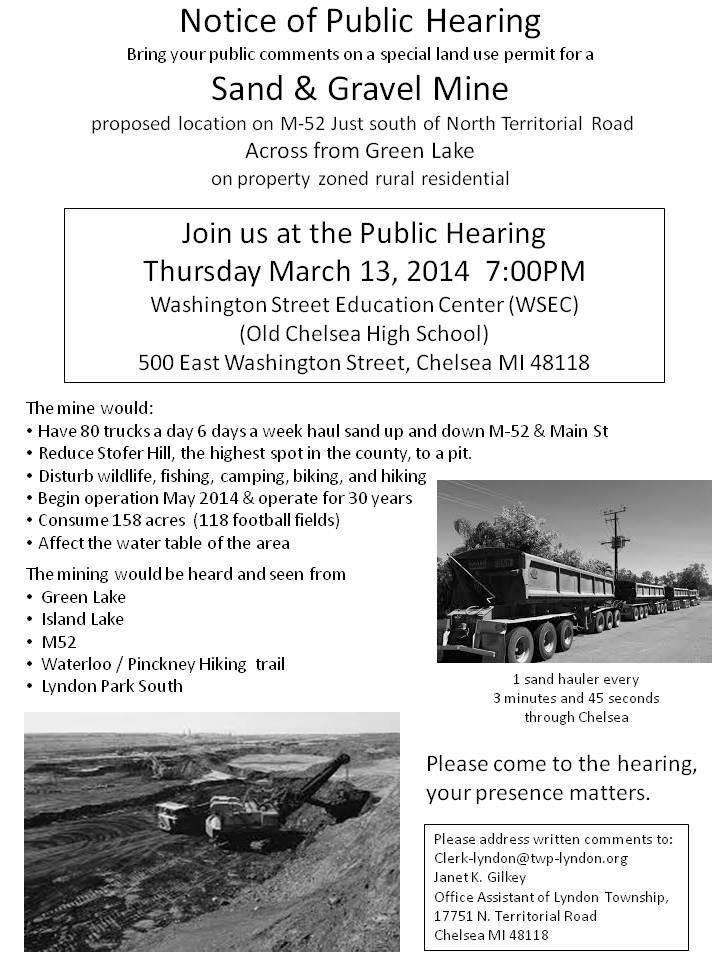

At the first public hearing on this permit, so many people turned out that not everyone was able to speak. A second hearing is scheduled for this Thursday, March 13. It will start at 7 p.m. at the Washington Street Education Center (the old Chelsea High School) at 500 E. Washington Street in Chelsea. Click the image at the right for a larger version of the flyer.

At the first public hearing on this permit, so many people turned out that not everyone was able to speak. A second hearing is scheduled for this Thursday, March 13. It will start at 7 p.m. at the Washington Street Education Center (the old Chelsea High School) at 500 E. Washington Street in Chelsea. Click the image at the right for a larger version of the flyer.

If you are unable to attend but wish to express your opinion about the issuance of the special use permit and a mineral mining operations permit to McCoig Gravel, written comments can be mailed or emailed as long as they are received by noon on March 13th. Email comments to clerk-lyndon@twp-lyndon.org or mail them to:

Lyndon Township Planning Commission and Lyndon Township Board

17751 N. Territorial Road

Chelsea, MI 48118

You can read a good summary of the issues from the perspective of local residents fighting the mine HERE. The Lyndon Township website has the McCoig application and supporting documentation.

At the end of the day, this comes down to Michigan law preventing local residents, through their elected government officials, from being able to have local control over the industrial operations that affect their daily lives. It puts burdens on the local government — with budgets that are stretched further and further thanks to Republicans’ actions — that should logically be borne by those that want a variance from the law that will benefit them financially. What happens in Lyndon Township could have broader implications, not the least of which would be a large, negative impact on surrounding communities like Dexter Township, Dexter Village, and Sylvan Township if a long-discussed by-pass around Chelsea is built. Even beyond the local area, the outcome may very well put in place a precedent that can be felt statewide.

One final thing: I’m told that if the Township denies the permits and is sued by the McCoig Gravel, they have to pay their own legal costs. However, if they approve and are sued by the township citizens, McCoig will pay their legal bills; a nice little financial incentive to approve the permits.